The Napoleonic Wars are military campaigns against several European coalitions led by France during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte (1799-1815). Napoleon's Italian campaign 1796-1797 and his Egyptian expedition of 1798-1799 in the concept of "Napoleonic wars" is usually not included, since they took place even before Bonaparte came to power (coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799). The Italian campaign is part of the Revolutionary Wars 1792-1799. The Egyptian expedition in different sources either refers to them, or is recognized as a separate colonial campaign.

Napoleon in the Council of Five Hundred and 18 Brumaires 1799

Napoleon's war with the Second Coalition

During the coup of 18 Brumaire (November 9) 1799 and the transfer of power in France to the first consul, citizen Napoleon Bonaparte, the republic was at war with the new (Second) European coalition, in which the Russian Emperor Paul I took part, who sent an army to the West under by the administration of Suvorov. Things went badly for France, especially in Italy, where Suvorov, together with the Austrians, conquered the Cisalpine Republic, after which a monarchist restoration took place in Naples, abandoned by the French, accompanied by bloody terror against the friends of France, and then the fall of the republic in Rome took place. Dissatisfied, however, with his allies, mainly Austria, and partly with England, Paul I left the coalition and the war, and when the first consul Bonaparte let the Russian prisoners go home without ransom and re-equipped, the Russian emperor even began to draw closer to France, very pleased that in this country "anarchy was replaced by a consulate." Napoleon Bonaparte himself willingly walked towards rapprochement with Russia: in fact, the expedition to Egypt undertaken by him in 1798 was directed against England in her Indian possessions, and in the imagination of the ambitious conqueror now a Franco-Russian campaign against India was drawn, the same as later, when the memorable war of 1812 began. This combination, however, did not take place, since in the spring of 1801 Paul I fell victim to a conspiracy, and power in Russia passed to his son Alexander I.

Napoleon Bonaparte - First Consul. Painting by J. O.D. Ingres, 1803-1804

After Russia left the coalition, Napoleon's war against other European powers continued. The first consul turned to the sovereigns of England and Austria with an invitation to end the struggle, but in response, unacceptable conditions were set for him - restoration Bourbons and the return of France to its former borders. In the spring of 1800 Bonaparte personally led an army into Italy and in the summer, after Battle of Marengo, took possession of all of Lombardy, while another French army occupied southern Germany and began to threaten Vienna itself. Peace of Luneville 1801 ended the war of Napoleon with Emperor Franz II and confirmed the terms of the previous Austro-French treaty ( Campoformian 1797 G.). Lombardy became the Italian Republic, which made its president the first consul Bonaparte. Both in Italy and in Germany, a number of changes were made after this war: for example, the Duke of Tuscan (from the Habsburg surname) received the principality of the Archbishop of Salzburg in Germany for renouncing his duchy, and Tuscany, under the name of the Kingdom of Etruria, was transferred to the Duke of Parma (from the Spanish line Bourbons). Most of the territorial changes were made after this war of Napoleon in Germany, many sovereigns of which, for the cession of the left bank of the Rhine to France, were to receive rewards at the expense of smaller princes, sovereign bishops and abbots, as well as free imperial cities. In Paris, a real bargaining in territorial increments opened, and Bonaparte's government took advantage of the rivalry of the German princes with great success in order to conclude separate treaties with them. This was the beginning of the destruction of the medieval Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, which, however, even earlier, as the witches said, was neither sacred, nor Roman, nor empire, but some kind of chaos from approximately the same number of states as there are days in a year. Now, at least purely, they have been greatly reduced, thanks to the secularization of spiritual principalities and the so-called mediatization - the transformation of direct (immediacy) members of the empire into mediocre (media) ones - various state trifles, such as small counties and imperial cities.

The war between France and England ended only in 1802, when both states concluded peace in Amiens... The first consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, then acquired the glory of a peacemaker after a ten-year war, which France had to wage: a life-long consulate was, in fact, a reward for the conclusion of peace. But the war with England soon resumed, and one of the reasons for this was that Napoleon, not content with the presidency in the Republic of Italy, also established his protectorate over the Batavian Republic, that is, Holland, very close to England. The renewal of the war took place in 1803, and the English king George III, who was at the same time the Elector of Hanover, lost his ancestral possession in Germany. After that, Bonaparte's war with England did not stop until 1814.

Napoleon's war with the Third Coalition

The war was the favorite work of the emperor-commander, equal to whom history generally knows little, and his unauthorized actions, which include assassination of the Duke of Enghien, which caused general indignation in Europe, soon forced the other powers to unite against the daring "upstart Corsican". His acceptance of the imperial title, the transformation of the Italian Republic into a kingdom, the sovereign of which was Napoleon himself, who was crowned in 1805 in Milan with the old iron crown of the Lombard kings, preparation of the Batavian Republic for the transformation into the kingdom of one of his brothers, as well as various other actions of Napoleon in relation to other countries were the reasons for the formation against him of the Third anti-French coalition from England, Russia, Austria, Sweden and the Kingdom of Naples, and Napoleon, for his part, secured in the coming coalition war alliances with Spain and with the South German princes (the sovereigns of Baden, Württemberg, Bavaria, Gessen and others), who, thanks to him, significantly increased their holdings by secularization and mediatization of smaller holdings.

War of the Third Coalition. Map

In 1805, Napoleon was preparing in Boulogne to land in England, but in fact he moved his troops to Austria. However, the landing in England and the war on its very territory soon became impossible, as a result of the extermination of the French fleet by the English under the command of Admiral Nelson at Trafalgar... But Bonaparte's land war with the Third Coalition was a series of brilliant victories. In October 1805, on the eve of Trafalgar, the Austrian army surrendered in Ulm, Vienna was taken in November, December 2, 1805, on the first anniversary of Napoleon's coronation, the famous "battle of the three emperors" took place at Austerlitz (see the article The Battle of Austerlitz), which ended in the complete victory of Napoleon Bonaparte over the Austro-Russian army, with which there were Franz II, and young Alexander I. Graduated from the war with the Third Coalition The world of presburg deprived the Habsburg monarchy of all of Upper Austria, Tyrol and Venice with its region and gave Napoleon the right to widely dispose of in Italy and Germany.

Triumph of Napoleon. Austerlitz. Artist Sergei Prisekin

Bonaparte's war with the Fourth Coalition

The next year, the enemies of France were joined by the Prussian king Frederick William III - thus the Fourth Coalition was formed. But the Prussians also suffered, in October of this year, a terrible defeat at Jena, after which the German princes, who were in an alliance with Prussia, were defeated, and during this war Napoleon occupied first Berlin, then Warsaw, which belonged to Prussia after the third partition of Poland. The assistance provided to Frederick William III by Alexander I was not successful, and in the war of 1807 the Russians were defeated under Friedland, after which Napoleon occupied Königsberg as well. Then the famous Peace of Tilsit took place, which ended the war of the Fourth Coalition and was accompanied by a meeting between Napoleon Bonaparte and Alexander I in a pavilion arranged in the middle of the Niemen.

War of the Fourth Coalition. Map

In Tilsit, it was decided by both sovereigns to help each other, dividing the West and the East between themselves. Only the intercession of the Russian tsar before the formidable victor saved Prussia from disappearing from the political map of Europe after this war, but this state still lost half of its possessions, had to pay a large indemnity and took over French garrisons.

Rebuilding Europe after the wars with the Third and Fourth coalitions

After the wars with the Third and Fourth coalitions, the Presburg and Tilsit worlds, Napoleon Bonaparte was the complete master of the West. The Venetian region increased the Kingdom of Italy, where Napoleon's stepson Eugene Beauharnais was made viceroy, and Tuscany was directly annexed to the French Empire itself. On the very next day after the Peace of Presburg, Napoleon announced that “the Bourbon dynasty had ceased to reign in Naples,” and sent his elder brother Joseph (Joseph) to reign there. The Batavian Republic was turned into a Dutch kingdom with Napoleon's brother Louis (Louis) on the throne. From the regions taken from Prussia to the west of the Elbe with neighboring parts of Hanover and other principalities, the Kingdom of Westphalia was created, which was received by another brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, Jerome (Jerome), from the former Polish lands of Prussia - Duchy of Warsaw, given to the sovereign of Saxony. Back in 1804, Franz II declared the imperial crown of Germany, the former electoral, the hereditary heritage of his house, and in 1806 he removed Austria from Germany and began to be titled not Roman, but Austrian emperor. In Germany itself, after these wars of Napoleon, a complete reshuffle was carried out: again some principalities disappeared, others received an increase in their possessions, in particular Bavaria, Württemberg and Saxony, even raised to the rank of kingdoms. The Holy Roman Empire was no longer there, and the Confederation of the Rhine was now organized in the western part of Germany - under the protectorate of the French emperor.

By the Peace of Tilsit, Alexander I was given, in agreement with Bonaparte, to increase his possessions at the expense of Sweden and Turkey, from which he took away, from the first in 1809 Finland, turned into an autonomous principality, from the second - after the Russian-Turkish war of 1806-1812 - Bessarabia incorporated directly into Russia. In addition, Alexander I undertook to annex his empire to the "continental system" of Napoleon, as the termination of all trade relations with England was called. The new allies were, in addition, forced to the same Sweden, Denmark and Portugal, which continued to stand on the side of England. A coup d'état took place in Sweden at this time: Gustav IV was replaced by his uncle Charles XIII, and the French Marshal Bernadotte was declared his heir, after which Sweden also went over to the side of France, as did Denmark after England attacked her for a desire to remain neutral. Since Portugal opposed, Napoleon, having entered into an alliance with Spain, announced that "the House of Braganza has ceased to reign", and began the conquest of this country, which forced her king with the whole family to sail to Brazil.

The beginning of Napoleon Bonaparte's war in Spain

Soon it was the turn of Spain to turn into the kingdom of one of the brothers of Bonaparte, the ruler of the European West. There was strife in the Spanish royal family. The government was, in fact, governed by Minister Godoy, the beloved of Queen Marie Louise, the wife of the close-minded and weak-willed Charles IV, an ignorant, short-sighted and shameless man, who since 1796 completely subordinated Spain to French politics. The royal couple had a son, Ferdinand, whom his mother and her favorite did not like, and so both sides began to complain to Napoleon one against the other. Bonaparte connected Spain with France even more closely when he promised Godoy to divide her possessions with Spain for his help in the war with Portugal. In 1808, members royal family were invited to negotiate in Bayonne, and here the matter ended with the deprivation of Ferdinand of his hereditary rights and the abdication of Charles IV himself from the throne in favor of Napoleon, as "the only sovereign capable of giving prosperity to the state." The result of the "Bayonne catastrophe" was the transfer of the Neapolitan king Joseph Bonaparte to the Spanish throne, with the transfer of the Neapolitan crown to Napoleon's son-in-law, Joachim Murat, one of the heroes of the 18th Brumaire coup. Somewhat earlier, in the same 1808, French soldiers occupied the Papal States, and the next year it was included in the French Empire, depriving the Pope of secular power. The fact is that Pope Pius VII considering himself an independent sovereign, he did not follow Napoleon's instructions in everything. "Your Holiness," Bonaparte once wrote to the Pope, "enjoys the supreme power in Rome, but I am the Emperor of Rome." Pius VII responded to the deprivation of power by excommunicating Napoleon from the church, for which he was forcibly transported to live in Savona, and the cardinals were resettled to Paris. Rome was then declared the second city of the empire.

Erfurt Date 1808

In the interval between the wars, in the fall of 1808, in Erfurt, which Napoleon Bonaparte left directly behind him, as the possession of France in the very heart of Germany, a famous meeting took place between the Tilsit allies, accompanied by a congress of many kings, sovereign princes, crown princes, ministers, diplomats and generals ... This was a very impressive demonstration of both the strength that Napoleon had in the West and his friendship with the sovereign, to whom the East was placed at the disposal. England was invited to begin negotiations to end the war on the basis of preserving for the negotiators who will own at the time of the conclusion of the peace, but England rejected this proposal. The sovereigns of the Confederation of the Rhine kept themselves Erfurt Congress before Napoleon completely, like servile courtiers before their master, and for the greater humiliation of Prussia, Bonaparte arranged a hare hunt on the battlefield of Jena, inviting a Prussian prince, who had come to seek relief from the difficult conditions of 1807. Meanwhile, an uprising broke out in Spain against the French, and in the winter from 1808 to 1809 Napoleon was forced to personally go to Madrid.

Napoleon's war with the Fifth Coalition and his conflict with Pope Pius VII

Counting on the difficulties that Napoleon met in Spain, the Austrian emperor in 1809 decided on a new war with Bonaparte ( War of the Fifth Coalition), but the war was again unsuccessful. Napoleon occupied Vienna and inflicted an irreparable defeat on the Austrians at Wagram. After the end of this war Schönbrunn Peace Austria again lost several territories divided between Bavaria, the Kingdom of Italy and the Duchy of Warsaw (by the way, it acquired Krakow), and one area, the coast of the Adriatic Sea, called Illyria, became the property of Napoleon Bonaparte himself. At the same time, Franz II had to give his daughter Maria Louise to Napoleon in marriage. Even earlier, Bonaparte became related through members of his family with some of the sovereigns of the Union of Rhine, and now he himself conceived of marrying a real princess, especially since his first wife, Josephine Beauharnais, was barren, and he wanted to have an heir to his blood. (At first he wooed the Russian Grand Duchess, the sister of Alexander I, but their mother was strongly against this marriage). In order to marry an Austrian princess, Napoleon had to divorce Josephine, but then there was an obstacle on the part of the pope, who did not agree to a divorce. Bonaparte neglected this and forced the French clergy under his control to divorce him from his first wife. This further exacerbated the relationship between him and Pius VII, who took revenge on him for depriving him of secular power and therefore, by the way, refused to consecrate bishops to persons whom the emperor appointed to the vacant cathedra. The quarrel between the emperor and the pope, by the way, led to the fact that in 1811 Napoleon organized a council of French and Italian bishops in Paris, who, under his pressure, issued a decree allowing archbishops to ordain bishops if the pope did not ordain government candidates for six months. Members of the cathedral, protesting against the capture of the pope, were imprisoned in the Vincennes castle (as before, the cardinals who did not appear at the wedding of Napoleon Bonaparte with Marie Louise were deprived of their red cassocks, for which they were mockingly called black cardinals). When a son was born to Napoleon from a new marriage, he received the title of Roman king.

The period of the highest power of Napoleon Bonaparte

This was the time of the greatest power of Napoleon Bonaparte, and after the war of the Fifth Coalition, he continued to be completely arbitrary in order in Europe. In 1810, he stripped his brother Louis of the Dutch crown for non-compliance with the continental system and annexed his kingdom directly to his empire; for the same, the entire coast of the German Sea was also taken away from the rightful owners (by the way, from the Duke of Oldenburg, a relative of the Russian sovereign) and annexed to France. France now included the coast of the German Sea, all of western Germany as far as the Rhine, parts of Switzerland, all of northwestern Italy and the Adriatic coast; northeastern Italy was the special kingdom of Napoleon, and his son-in-law and two brothers reigned in Naples, Spain and Westphalia. Switzerland, the Confederation of the Rhine, covered on three sides by Bonaparte's possessions, and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw were under his protectorate. Austria and Prussia, heavily curtailed after the Napoleonic wars, were squeezed, thus, between the possessions of either Napoleon himself or his vassals, while Russia, apart from Finland, had only the Bialystok and Tarnopol districts separated by Napoleon from Prussia and Austria in 1807 and 1809

Europe in 1807-1810. Map

The despotism of Napoleon in Europe was limitless. When, for example, the Nuremberg bookseller Palm refused to name the author of the booklet published by him "Germany in its greatest humiliation", Bonaparte ordered him to be arrested on foreign territory and brought to court-martial, which sentenced him to death (which was like a repetition of the episode with the Duke of Enghien).

On the mainland Western Europe after the Napoleonic wars everything, so to speak, was turned upside down: the borders were confused; some old states were destroyed and new ones were created; even many geographical names etc. The secular power of the pope and the medieval Roman Empire no longer existed, as did the spiritual principalities of Germany and its many imperial cities, these purely medieval city republics. In the territories inherited by France itself, in the states of Bonaparte's relatives and clientele, a number of reforms were carried out according to the French model - reforms of administrative, judicial, financial, military, school, ecclesiastical, often with the abolition of the estate privileges of the nobility, limitation of the power of the clergy, the destruction of many monasteries , the introduction of religious tolerance, etc., etc. One of the remarkable features of the era of the Napoleonic Wars was the abolition of the serfdom of the peasants in many places, sometimes immediately after the wars by Bonaparte himself, as was the case in the Duchy of Warsaw at its very foundation. Finally, outside the French empire, the French civil code was also enacted, “ Napoleonic Code”, Which here and there continued to operate even after the collapse of the empire of Napoleon, as it was in the western parts of Germany, where it was in use until 1900, or as it is still the case in the Kingdom of Poland, formed from the Grand Duchy of Warsaw in 1815. It must also be added that during the Napoleonic Wars in different countries, in general, French administrative centralization was very willingly adopted, which was distinguished by simplicity and harmony, strength and speed of action and was therefore an excellent instrument of government influence on subjects. If the republics are daughters at the end of the 18th century. were settled in the image and likeness of France at that time, their common mother, and now the states that Bonaparte put into the management of his brothers, son-in-law and stepson, received representative institutions for the most part according to the French model, that is, with a purely ghostly, decorative character. Such a device was introduced precisely in the kingdoms of Italy, Holland, Neapolitan, Westphalian, Spanish, etc. In fact, the very sovereignty of all these political creations of Napoleon was illusory: everywhere one will reigned, and all these sovereigns, relatives of the emperor of the French and his vassals were obliged to deliver a lot of money and a lot of soldiers to their supreme overlord for new wars - no matter how much he demanded.

Guerrilla war against Napoleon in Spain

It became painful for the conquered peoples to serve the goals of a foreign conqueror. While Napoleon dealt in wars only with sovereigns who relied on only armies and were always ready to receive increments of their possessions from his hands, it was easy for him to cope with them; in particular, for example, the Austrian government preferred to lose province after province, so long as the subjects sat quietly, which the Prussian government was very busy with before the defeat of Jena. Real difficulties began to be created for Napoleon only when the peoples began to revolt and wage a petty partisan war against the French. The first example of this was provided by the Spaniards in 1808, then by the Tyroleans during the Austrian War of 1809; to an even greater extent the same took place in Russia in 1812. Events in 1808-1812. in general, they showed the governments what their strength could only be.

The Spaniards, who were the first to set an example of the people's war (and whose resistance was helped by England, who did not spare money at all to fight France), gave Napoleon a lot of worries and troubles: in Spain he had to suppress the uprising, wage a real war, conquer the country and by military force support the throne of Joseph Bonaparte. The Spaniards even created general organization for waging their little wars, these famous "guerillas", which, due to our unfamiliarity with the Spanish language, later turned into some kind of "guerillas", in the sense of partisan detachments or participants in the war. The Guerilles were one; the other was the Cortes, convened by the provisional government, or regency in Cadiz, under the protection of the English fleet, the popular representation of the Spanish nation. They were collected in 1810, and in 1812 they made the famous Spanish constitution, very liberal and democratic at that time, using the model of the French constitution of 1791 and some of the features of the medieval Aragonese constitution.

Movement against Bonaparte in Germany. Prussian reformers Hardenberg, Stein and Scharnhorst

Considerable fermentation also took place among the Germans, who were eager to get out of their humiliation through a new war. Napoleon knew about this, but he fully relied on the loyalty of the sovereigns of the Rhine League and on the weakness of Prussia and Austria after 1807 and 1809, and the ostracism that cost the life of the unfortunate Palma was supposed to serve as a warning that every German who dared to become enemy of France. During these years, the hopes of all German patriots hostile to Bonaparte were pinned on Prussia. This state, so exalted in the second half of the XVIII century. The victories of Frederick the Great, reduced by a whole half after the war of the Fourth Coalition, was in the greatest humiliation, the way out of which was only in internal reforms. Among the king's ministers Frederick Wilhelm III there were people who just stood for the need for serious transformations, and among them the most outstanding were Hardenberg and Stein. The first of them was a great admirer of new French ideas and orders. In 1804-1807. he held the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs and in 1807 proposed to his sovereign a whole plan of reforms: the introduction in Prussia of popular representation with strictly, however, centralized management according to the Napoleonic model, the abolition of noble privileges, the emancipation of the peasants from serfdom, the elimination of the constraints that lay on industry and trade. Considering Hardenberg his enemy, which he really was, Napoleon demanded that Frederick Wilhelm III, at the end of the war with him in 1807, that this minister be given a resignation, and advised him to take Stein in his place, as a very efficient person, not knowing that he was also an enemy of France. Baron Stein had previously been a minister in Prussia, but did not get along with the court spheres, and even with the king himself, and received a resignation. In contrast to Hardenberg, he was opposed to administrative centralization and stood for the development of self-government, as in England, with the preservation, within certain limits, of class, guilds, etc., but he was a man of a greater mind than Hardenberg, and showed a greater ability to development in a progressive direction to the extent that life itself pointed out to him the need to destroy antiquity, remaining, however, still an enemy of the Napoleonic system, since he wanted the initiative of society. Appointed minister on October 5, 1807, Stein, on the 9th of the same month, published a royal edict abolishing serfdom in Prussia and allowing non-nobles to acquire noble lands. Further, in 1808, he began to implement his plan to replace the bureaucratic system of government with local self-government, but managed to give the latter only to the cities, while the villages and regions remained under the old order. He also thought about government representation, but of a purely deliberative nature. Stein did not remain in power for long: in September 1808, the French official newspaper published his letter intercepted by the police, from which Napoleon Bonaparte learned that the Prussian minister strongly recommended the Germans to follow the example of the Spaniards. After this and another article hostile to him in a French government body, the reformer minister was forced to resign, and after a while Napoleon even directly declared him an enemy of France and the Rhine Union, his estates confiscated and himself subject to arrest, so that Stein had to flee and hide in various cities of Austria, until in 1812. he was not summoned to Russia.

After one insignificant minister who replaced such an important person, Frederick William III again called Hardenberg to power, who, being a supporter of the Napoleonic system of centralization, began to transform the Prussian administration in this direction. In 1810, the king, at his insistence, promised to give his subjects even national representation, and with the aim of both developing this issue and introducing other reforms in 1810 - 1812. convened in Berlin meetings of notables, that is, representatives of the estates at the choice of the government. More detailed legislation on the redemption of peasant duties in Prussia also dates back to this time. The military reform carried out by the general was also important for Prussia. Scharnhorst; according to one of the conditions of the Tilsit peace, Prussia could not have more than 42 thousand troops, and such a system was invented: universal conscription was introduced, but the periods of stay of soldiers in the army were greatly reduced so that, having trained them in military affairs, they could take new ones in their place , and enrolled trained in the reserve, so that Prussia, if necessary, could have a very large army. Finally, in the same years, according to the plan of the enlightened and liberal Wilhelm von Humboldt, the University in Berlin was founded, and the famous philosopher Fichte read his patriotic "Speeches to the German Nation" to the sound of the drums of the French garrison. All these phenomena, which characterize the internal life of Prussia after 1807, made this state the hope of the majority of German patriots hostile to Napoleon Bonaparte. Among the interesting manifestations of the liberation mood of that time in Prussia, it is necessary to include the education in 1808. Tugendbund, or the Union of Valor, secret society, which included scientists, military, officials and whose goal was the revival of Germany, although in fact the union did not play a big role. The Napoleonic police followed the German patriots, and, for example, Stein's friend Arndt, author of the spirit of the time imbued with national patriotism, had to flee from Napoleon's wrath to Sweden in order not to suffer the sad fate of Palma.

The national excitement of the Germans against the French began to intensify since 1809. Beginning this year, the war with Napoleon, the Austrian government had already explicitly set its goal as the liberation of Germany from the foreign yoke. In 1809, uprisings against the French broke out in Tyrol under the leadership of Andrei Gopher, in Stralsund, which was seized by the insanely brave Major Schill, in Westphalia, where the "black legion of revenge" of the Duke of Braunschweig was operating, etc., but Gopher was executed, Schill killed in a military battle, the Duke of Brunswick had to flee to England. At the same time, in Schönbrunn, an attempt was made on the life of Napoleon by one young German, Staps, who was then executed for this. “Fermentation has reached the highest degree,” his brother, the King of Westphalia once wrote to Napoleon Bonaparte, “the most reckless hopes are accepted and supported; They set themselves up as a model for Spain, and, believe me, when the war begins, the countries between the Rhine and the Oder will be the theater of a great uprising, for one should fear the extreme despair of peoples who have nothing to lose. " This prediction came true after the failure of the campaign to Russia undertaken by Napoleon in 1812 and the former, according to the apt expression of the Minister of Foreign Affairs Talleyrand, "The beginning of the end".

Relationship of Napoleon Bonaparte with Tsar Alexander I

In Russia, after the death of Paul I, who was thinking about rapprochement with France, "the days of the Alexandrovs had a wonderful beginning." The young monarch, a pupil of the republican Laharpe, who himself almost considered himself a republican, at least the only one in the entire empire, and in other respects recognized itself as a "happy exception" to the throne, from the very beginning of his reign made plans for internal reforms - right up to the end after all, before the introduction of the constitution in Russia. In 1805-07. he was in a war with Napoleon, but in Tilsit they entered into an alliance with each other, and two years later in Erfurt they cemented their friendship in the face of the whole world, although Bonaparte immediately guessed in his friend-rival the "Byzantine Greek" (and himself, however, being, according to Pope Pius VII, a comedian). And Russia in those years had its own reformer, who, like Hardenberg, bowed before Napoleonic France, but much more original. This reformer was the famous Speransky, the author of a whole plan for the state transformation of Russia on the basis of representation and separation of powers. Alexander I brought him closer to him at the beginning of his reign, but Speransky began to use a particularly strong influence on his sovereign during the years of Russia's rapprochement with France after the Peace of Tilsit. By the way, when Alexander I, after the war of the Fourth Coalition, went to Erfurt to meet with Napoleon, he took Speransky with him along with other confidants. But then this outstanding statesman was overtaken by the tsarist disfavor, just at the very time that relations between Alexander I and Bonaparte deteriorated. It is known that Speransky in 1812 was not only removed from the case, but also had to go into exile.

The relationship between Napoleon and Alexander I soured for many reasons, including the main role played Russia's non-observance of the continental system in all its severity, the hope of the Poles on the part of Bonaparte regarding the restoration of their former fatherland, the seizure of possessions by France from the Duke of Oldenburg, who was related to the Russian royal family, etc. In 1812, things came to a complete rupture and the war that was "the beginning of the end."

A murmur against Napoleon in France

Prudent people have long predicted that sooner or later there will be a disaster. Even during the proclamation of the empire, Cambaceres, who was one of the consuls with Napoleon, said to another, Lebrun: “I have a premonition that what is being built now will not be durable. We fought a war with Europe in order to impose republics on it as daughters of the French Republic, and now we will wage a war in order to give her monarchs, sons or our brothers, and it will end with France, exhausted by wars, falling under the weight of these insane enterprises. ". “You are happy,” Minister of the Sea, Dekres, once said to Marshal Marmont, because now you have been made a Marshal, and everything seems to you in a rosy light. But don't you want me to tell you the truth and pull back the veil behind which the future is hidden? The emperor went crazy, completely crazy: all of us, how many of us are, he will make us fly head over heels, and all this will end in a terrible catastrophe. Before the Russian campaign of 1812 and in France itself, some opposition began to appear against the constant wars and despotism of Napoleon Bonaparte. It was already mentioned above that Napoleon met with a protest against his treatment of the Pope by some members of the church council, which he convened in Paris in 1811, and in the same year a deputation from the Paris Chamber of Commerce with the idea of ruinousness came to him. continental system for French industry and trade. The population began to be weighed down by the endless wars of Bonaparte, the increase in military spending, the growth of the army, and already in 1811 the number of those who avoided military service reached almost 80 thousand people. In the spring of 1812, a dull murmur in the Parisian population forced Napoleon to move to Saint-Cloud especially early, and only with such a mood of the people could a general, named Malet, have the daring idea of using Napoleon's war in Russia to carry out a coup d'état in Paris with the aim of restoring the republic. Suspected of being unreliable, Male was arrested, but escaped from his confinement, appeared in some barracks and there announced to the soldiers the death of the "tyrant" Bonaparte, who allegedly ended his life in a distant military campaign. Part of the garrison went to Male, and he, having then prepared a forged senatus consultant, was already preparing to organize a provisional government, when he was captured and, along with his accomplices, was put on a military court, which sentenced all of them to death. Upon learning of this conspiracy, Napoleon was extremely annoyed that some even representatives of the authorities believed the attackers, and that the public was rather indifferent to all this.

Napoleon's campaign to Russia 1812

Male's conspiracy dates back to the end of October 1812, when the failure of Napoleon's campaign against Russia had already been sufficiently revealed. Of course, the military events of this year are too well known to be necessary in their detailed exposition, and therefore it remains only to recall the main moments of the war with Bonaparte of 1812, them "twelve languages".

In the spring of 1812, Napoleon Bonaparte concentrated large military forces in Prussia, which was forced, like Austria, to enter into an alliance with him, and in the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, and in mid-June, his troops, without declaring war, entered the then borders of Russia. Napoleon's "great army" of 600 thousand people consisted only of half of the French: the rest were various other "peoples": Austrians, Prussians, Bavarians, etc., that is, in general, subjects of Napoleon Bonaparte's allies and vassals. The Russian army, which was three times smaller and, moreover, scattered, had to retreat at the beginning of the war. Napoleon quickly began to occupy one city after another, mainly on the way to Moscow. Only at Smolensk did the two Russian armies manage to connect, which, however, were unable to stop the enemy's advance. Kutuzov's attempt to detain Bonaparte at Borodino (see the articles The Battle of Borodino in 1812 and the Battle of Borodino in 1812 - briefly), made at the end of August, was also unsuccessful, and at the beginning of September Napoleon was already in Moscow, from where he thought to dictate the terms of peace to Alexander I. But just at this time the war with the French became popular. After the battle near Smolensk, the inhabitants of the areas through which the army of Napoleon Bonaparte moved, began to burn everything in its path, and with its arrival in Moscow, fires began in this ancient capital of Russia, from where most of the population left. Little by little, the city was almost completely burned down, the reserves that it had were depleted, and the supply of new ones was hampered by Russian partisan detachments, which unleashed a war on all the roads that led to Moscow. When Napoleon was convinced of the futility of his hope that they would ask for peace from him, he himself wished to enter into negotiations, but from the Russian side he did not meet the slightest desire to conclude peace. On the contrary, Alexander I decided to wage war until the final expulsion of the French from Russia. While Bonaparte was inactive in Moscow, the Russians began to prepare to completely cut off Napoleon's exit from Russia. This plan did not come true, but Napoleon realized the danger and hastened to leave the devastated and burned-out Moscow. At first, the French made an attempt to break through to the south, but the Russians cut off the road in front of them when Maloyaroslavets, and the remnants of the great army of Bonaparte had to retreat along the former, devastated Smolensk road with a very harsh winter that began early this year. The Russians followed this disastrous retreat almost on their heels, inflicting defeat after defeat on the lagging troops. Napoleon himself, who happily escaped captivity while crossing his army across the Berezina, abandoned everything in the second half of November and left for Paris, only now deciding to officially notify France and Europe of the failure that befell him during the Russian war. The retreat of the remnants of Bonaparte's great army was now a real escape amid the horrors of cold and hunger. On December 2, less than six full months after the start of the Russian war, the last troops of Napoleon crossed the Russian border back. After that, the French had no choice but to abandon the Grand Duchy of Warsaw to the mercy of fate, the capital of which was occupied by the Russian army in January 1813.

The crossing of Napoleon's army across the Berezina. Painting by P. von Hess, 1844

Foreign campaign of the Russian army and the War of the Sixth Coalition

When Russia was completely cleared of the enemy hordes, Kutuzov advised Alexander I to limit himself to this and stop further war. But in the soul of the Russian sovereign, a mood prevailed, forcing him to postpone military operations against Napoleon outside Russia. In this latter intention, the emperor was strongly supported by the German patriot Stein, who found shelter against the persecution of Napoleon in Russia and to a certain extent subordinated Alexander to his influence. The failure of the war of the great army in Russia made a great impression on the Germans, among whom national enthusiasm was spreading more and more, the patriotic lyrics of Kerner and other poets of the era remained a monument. At first, the German governments did not dare, however, to follow their subjects, who rose up against Napoleon Bonaparte. When, at the very end of 1812, the Prussian general York, on his own fear, concluded a convention with the Russian general Diebitsch in Taurogen and stopped the struggle for the cause of France, Frederick William III Stein's thoughts, the provincial militia for the war against the enemy of the German nation. It was only when the Russians entered Prussian territory that the king, forced to choose between an alliance with either Napoleon or Alexander I, leaned towards the latter, and even then not without some hesitation. In February 1813, in Kalisz, Prussia concluded a military treaty with Russia, accompanied by an appeal by both sovereigns to the population of Prussia. Then, Frederick William III declared war on Bonaparte, and a special royal proclamation to his loyal subjects was published. In this and other proclamations, with which the new allies also addressed the population of other parts of Germany and in the compilation of which Stein played an active role, much was said about the independence of peoples, about their right to control their fate, about the power of public opinion, before which the sovereigns themselves must bow , etc.

From Prussia, where, next to the regular army, detachments of volunteers were formed from people of every rank and state, often not Prussian subjects, the national movement began to be transferred to other German states, whose governments, on the contrary, remained loyal to Napoleon Bonaparte and restrained manifestations in their possessions. German patriotism. Meanwhile, Sweden, England and Austria joined the Russian-Prussian military alliance, after which the members of the Rhine Union began to fall away from their allegiance to Napoleon - under the condition of the inviolability of their territories or, at least, equivalent rewards in cases where some or changes in the boundaries of their possessions. So it was formed Sixth coalition against Bonaparte. Three-day (October 16-18) battle with Napoleon at Leipzig, which was unfavorable for the French and forced them to start retreating to the Rhine, resulted in the destruction of the Rhine Union, the return to their possessions of the dynasties expelled during the Napoleonic wars and the final transition to the side of the anti-French coalition of the South German rulers.

By the end of 1813, the lands east of the Rhine were free of the French, and on the night of January 1, 1814, part of the Prussian army under the command of Blucher crossed this river, which then served as the eastern border of Bonaparte's empire. Even before the Battle of Leipzig, the allied sovereigns offered Napoleon to enter into peace negotiations, but he did not agree to any conditions. Before transferring the war to the territory of the empire itself, Napoleon was once again offered peace on the condition of preserving the Rhine and Alpine borders for France, but only giving up domination in Germany, Holland, Italy and Spain, but Bonaparte continued to persist, although in France itself the public the opinion considered these conditions quite acceptable. A new peace proposal in mid-February 1814, when the Allies were already in French territory, likewise came to nothing. The war went on with varying happiness, but one defeat of the French army (at Arsy-sur-Aube on March 20-21) opened the way for the Allies to Paris. On March 30, they took the Montmartre heights dominating over this city by attack, and on the 31st, their solemn entry into the city took place.

Deposition of Napoleon in 1814 and restoration of the Bourbons

The next day after this, the Senate proclaimed the deposition of Napoleon Bonaparte from the throne with the formation of a provisional government, and two days later, that is, on April 4, he himself, in the Château de Fontainebleau, abdicated the throne in favor of his son after he learned about the transition of Marshal Marmont to the side of the Allies. The latter were not content with this, however, and a week later Napoleon was forced to sign an act of unconditional abdication. The title of the emperor was retained for him, but he had to live on the island of Elbe, which was given to him. During these events, the fallen Bonaparte was already the subject of extreme hatred of the population of France, as the culprit of devastating wars and enemy invasion.

The Provisional Government, formed after the end of the war and the deposition of Napoleon, drew up a draft of a new constitution, which was adopted by the Senate. Meanwhile, at that time, in agreement with the victors of France, the restoration of the Bourbons was already being prepared in the person of the brother of Louis XVI, who was executed during the Revolutionary Wars, who, after the death of his little nephew, who was recognized by the royalists as Louis XVII, began to be called Louis XVIII... The Senate proclaimed him king, freely called to the throne by the nation, but Louis XVIII wanted to reign solely by his inheritance right. He did not accept the Senate constitution, and instead granted (entrusted) his power to the constitutional charter, and even then under strong pressure from Alexander I, who agreed to restoration only under the condition of granting France a constitution. One of the main figures who were bustling after the end of the Bourbon War was Talleyrand, who said that only the restoration of the dynasty will be the result of the principle, all the rest is simple intrigue. With Louis XVIII returned his younger brother and heir, the Comte d'Artois, with his family, other princes and numerous émigrés from the most implacable representatives of pre-revolutionary France. The nation immediately felt that both the Bourbons and the émigrés in exile, in the words of Napoleon, "had forgotten nothing and learned nothing." Anxiety began throughout the country, numerous reasons for which were given by the statements and behavior of princes, returned nobles and clergy, clearly striving for the restoration of antiquity. The people even started talking about the restoration of feudal rights, etc. Bonaparte watched on his Elbe how irritation against the Bourbons grew in France, and at the congress that met in Vienna in the fall of 1814 to arrange European affairs, wrangling began, which could embroil the allies. In the eyes of the fallen emperor, these were favorable circumstances for the return of power in France.

"One Hundred Days" of Napoleon and the War of the Seventh Coalition

On March 1, 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte with a small detachment secretly left Elba and unexpectedly landed near Cannes, from where he moved to Paris. The former ruler of France brought with him proclamations to the army, to the nation, and to the population of the coastal departments. “I,” it was said in the second of them, “was enthroned by your election, and everything that was done without you is illegal ... feudal law, but it can secure the interests of only a small handful of enemies of the people! .. The French! in my exile, I heard your complaints and desires: you demanded the return of the government chosen by you and therefore the only legal one ”, etc. On the way of Napoleon Bonaparte to Paris, his small detachment grew from soldiers who joined him everywhere, and his new military campaign received kind of triumphal procession. In addition to the soldiers who adored their "little corporal", the people, who now saw in him a savior from the hated emigrants, also went over to Napoleon's side. Marshal Ney, sent against Napoleon, boasted before leaving that he would bring him in a cage, but then with his entire detachment went over to his side. On March 19, Louis XVIII hurriedly fled from Paris, having forgotten Talleyrand's reports from the Congress of Vienna and a secret treaty against Russia in the Tuilerand Palace, and the next day a crowd of people literally carried Napoleon into the palace in their arms, which had only been abandoned by the king the day before.

The return of Napoleon Bonaparte to power was the result not only of a military revolt against the Bourbons, but also of a popular movement that could easily turn into a real revolution. In order to reconcile with himself the educated classes and the bourgeoisie, Napoleon now agreed to a liberal reform of the constitution, calling to this cause one of the most prominent political writers of the era, Benjamena Constant, who earlier spoke out sharply against his despotism. A new constitution was even drawn up, which, however, received the name of an "additional act" to the "constitutions of the empire" (that is, to the laws of the VIII, X and XII years), and this act was submitted for the approval of the people, who adopted it with one and a half million votes ... On June 3, 1815, the opening of new representative chambers took place, in front of which, a few days later, Napoleon delivered a speech announcing the introduction of a constitutional monarchy in France. However, the emperor did not like the reciprocal addresses of the representatives and peers, since they contained warnings and admonitions, and he expressed his displeasure with them. However, he did not have a further continuation of the conflict, since Napoleon had to rush to the war.

The news of Napoleon's return to France forced the sovereigns and ministers who had gathered for the congress in Vienna to end the strife that had begun between them and to unite again in a general alliance for a new war with Bonaparte ( Seventh Coalition Wars). On June 12, Napoleon left Paris to go to his army, and on the 18th at Waterloo he was defeated by the Anglo-Prussian army under the command of Wellington and Blucher. In Paris, Bonaparte, defeated in this new short war, faced a new defeat: the House of Representatives demanded that he abdicate the throne in favor of his son, who was proclaimed emperor under the name of Napoleon II. The allies, who soon appeared under the walls of Paris, decided the matter differently, namely, they restored Louis XVIII. Napoleon himself, when the enemy approached Paris, thought to flee to America and for this purpose arrived in Rochefort, but was intercepted by the British, who placed him on the island of St. Helena. This secondary reign of Napoleon, accompanied by the War of the Seventh Coalition, lasted only about three months and was called in history the "hundred days". In his new imprisonment, the second deposed Emperor Bonaparte lived for about six years, having died in May 1821.

On June 24 (June 12, old style), 1812, the Patriotic War began - Russia's liberation war against Napoleonic aggression.

The invasion of the Russian Empire by the troops of the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was caused by the aggravation of Russian-French economic and political contradictions, the actual refusal of Russia to participate in the continental blockade (the system of economic and political measures used by Napoleon I in the war with England), etc.

Napoleon strove for world domination, Russia interfered with the implementation of his plans. He counted, having inflicted the main blow on the right flank of the Russian army in the general direction of Vilno (Vilnius), to defeat it in one or two general battles, to seize Moscow, force Russia to surrender and dictate to her a peace treaty on favorable terms.

June 24 (June 12, old style) 1812 Napoleon's "Great Army" without declaring war, having crossed the Niemen, invaded Russian Empire... It numbered over 440 thousand people and had a second echelon, in which there were 170 thousand people. The "Great Army" included the troops of all the countries of Western Europe conquered by Napoleon (French troops accounted for only half of its strength). She was opposed by three Russian armies, far apart from each other, with a total strength of 220-240 thousand people. Initially, only two of them acted against Napoleon - the first, under the command of Infantry General Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, covering the St. Petersburg direction, and the second, under the command of Infantry General Pyotr Bagration, focused on the Moscow direction. The third army of general from the cavalry Alexander Tormasov covered the southwestern borders of Russia and began hostilities at the end of the war. At the beginning of hostilities, the general leadership of the Russian forces was carried out by Emperor Alexander I, in July 1812 he transferred the main command to Barclay de Tolly.

Four days after the invasion of Russia, French troops occupied Vilna. On July 8 (June 26, old style) they entered Minsk.

Having figured out Napoleon's plan to separate the Russians of the first and second armies and defeat them one by one, the Russian command began a systematic withdrawal of them for connection. Instead of a phased dismemberment of the enemy, the French troops were forced to move behind the elusive Russian armies, stretching communications and losing superiority in forces. Retreating, the Russian troops fought rearguard battles (a battle undertaken with the aim of delaying the advancing enemy and thereby ensuring the retreat of the main forces), inflicting significant losses on the enemy.

To help the active army to repel the invasion of the Napoleonic army on Russia, on the basis of the manifesto of Alexander I of July 18 (July 6, old style) of 1812 and his appeal to the inhabitants of the "Capital of our Moscow" with an appeal to become the initiators, temporary armed formations began to form - the people's militia. This allowed the Russian government to mobilize large human and material resources for the war in a short time.

Napoleon tried to prevent the connection of the Russian armies. On July 20 (July 8, old style), the French occupied Mogilev and did not allow the Russian armies to connect in the Orsha region. Only thanks to stubborn rearguard battles and the high skill of maneuvering the Russian armies, which managed to upset the enemy's plans, they united on August 3 (July 22, according to the old style) near Smolensk, keeping their main forces combat-ready. The first big battle took place here. Patriotic War 1812 The Smolensk battle lasted three days: from 16 to 18 August (from 4 to 6 August according to the old style). The Russian regiments repelled all French attacks and retreated only by order, leaving the burning city to the enemy. Almost all the inhabitants left it with the troops. After the battles for Smolensk, the combined Russian armies continued to withdraw in the direction of Moscow.

The retreat strategy of Barclay de Tolly, unpopular neither in the army nor in Russian society, leaving the enemy a significant territory forced Emperor Alexander I to establish the post of commander-in-chief of all Russian armies and on August 20 (August 8, old style) to appoint infantry general Mikhail Golenishchev to it. Kutuzov, who had great combat experience and was popular both among the Russian army and among the nobility. The emperor not only put him in charge of the army in the field, but also subordinated the militias, reserves and civilian authorities to him in the war-torn provinces.

Based on the requirements of Emperor Alexander I, the mood of the army, eager to give the enemy a battle, the commander-in-chief Kutuzov decided, relying on a pre-selected position, 124 kilometers from Moscow, near the village of Borodino near Mozhaisk, to give the French army a general battle in order to inflict the greatest possible damage on it and stop the attack on Moscow.

By the beginning of the Battle of Borodino, the Russian army had 132 (according to other sources, 120) thousand people, the French - about 130-135 thousand people.

It was preceded by the battle for the Shevardinsky redoubt, which began on September 5 (August 24, according to the old style), in which Napoleon's troops, despite more than three-fold superiority in forces, only by the end of the day managed to master the redoubt with great difficulty. This battle allowed Kutuzov to unravel the plan of Napoleon I and to strengthen his left wing in a timely manner.

The battle of Borodino began at five o'clock in the morning on September 7 (August 26, old style) and lasted until 20 o'clock in the evening. Napoleon did not manage to break through the Russian position in the center for the whole day, nor to bypass it from the flanks. The private tactical successes of the French army - the Russians retreated from their original position by about one kilometer - did not become victorious for it. Late in the evening, the frustrated and bloodied French troops were withdrawn to their original positions. The Russian field fortifications they had taken were so destroyed that there was no point in holding them back. Napoleon never succeeded in defeating the Russian army. In the Battle of Borodino, the French lost up to 50 thousand people, the Russians - over 44 thousand people.

Since the losses in the battle turned out to be huge, and the reserves were used up, the Russian army withdrew from the Borodino field, retreating to Moscow, while waging rearguard battles. On September 13 (September 1, old style), at the military council in Fili, the decision of the commander-in-chief "for the sake of preserving the army and Russia" to leave Moscow to the enemy without a fight was supported by a majority vote. The next day, Russian troops left the capital. Together with them, most of the population left the city. On the very first day of the entry of French troops into Moscow, fires began, devastating the city. For 36 days, Napoleon languished in the burnt-out city, waiting in vain for an answer to his proposal to Alexander I about peace, on favorable terms for him.

The main Russian army, leaving Moscow, made a march and settled in the Tarutino camp, reliably covering the south of the country. From here, Kutuzov launched a small war with the forces of army partisan detachments. During this time, the peasantry of the Great Russian provinces, engulfed in war, rose to a large-scale people's war.

Attempts by Napoleon to enter into negotiations were rejected.

On October 18 (October 6, old style), after the battle on the Chernishna River (near the village of Tarutino), in which the vanguard of the "Great Army" under the command of Marshal Murat was defeated, Napoleon left Moscow and sent his troops towards Kaluga to break through into the southern Russian provinces rich in food resources. Four days after the departure of the French, the advance detachments of the Russian army entered the capital.

After the battle at Maloyaroslavets on October 24 (October 12, old style), when the Russian army blocked the enemy's path, Napoleon's troops were forced to start retreating along the ruined old Smolensk road. Kutuzov organized the pursuit of the French along the roads passing south of the Smolensk highway, acting with strong vanguards. Napoleon's troops lost people not only in clashes with their pursuers, but also from attacks by partisans, from hunger and cold.

To the flanks of the retreating French army, Kutuzov pulled up troops from the south and north-west of the country, which began to actively act and inflict defeat on the enemy. Napoleon's troops actually found themselves surrounded on the Berezina River near the city of Borisov (Belarus), where on November 26-29 (November 14-17, old style) they fought with the Russian troops, who were trying to cut off their escape routes. The French emperor, having misled the Russian command with a false crossing, was able to transfer the remnants of the troops across two hastily erected bridges across the river. On November 28 (November 16, old style), Russian troops attacked the enemy on both banks of the Berezina, but, despite the superiority of forces, due to indecision and incoherence of actions, they did not succeed. On the morning of November 29 (November 17, old style), the bridges were burned on the orders of Napoleon. On the left bank there were carts and crowds of lagging French soldiers (about 40 thousand people), most of whom drowned during the crossing or were captured, and the total losses of the French army in the battle of Berezina amounted to 50 thousand people. But Napoleon in this battle managed to avoid complete defeat and retreat to Vilna.

The liberation of the territory of the Russian Empire from the enemy ended on December 26 (December 14, old style), when Russian troops occupied the border towns of Bialystok and Brest-Litovsk. The enemy lost up to 570 thousand people on the battlefields. The losses of the Russian troops amounted to about 300 thousand people.

The official end of the Patriotic War of 1812 is considered to be the manifesto signed by Emperor Alexander I on January 6, 1813 (December 25, 1812 according to the old style), in which he announced that he had kept his promise not to end the war until the enemy was completely expelled from the territory of the Russian Federation. empire.

The defeat and death of the "Great Army" in Russia created the conditions for the liberation of the peoples of Western Europe from Napoleonic tyranny and predetermined the collapse of Napoleon's empire. The Patriotic War of 1812 showed the complete superiority of Russian military art over the military art of Napoleon, and caused a nationwide patriotic enthusiasm in Russia.

(Additional

Research by Archpriest Alexander Ilyashenko “Dynamics of the number and losses of the Napoleonic army in the Patriotic War of 1812”.

In 2012 it will be two hundred years old and. These events are described by many contemporaries and historians. However, despite many published sources, memoirs and historical studies, there is no established point of view either for the size of the Russian army and its losses in the Battle of Borodino, or for the number and losses of the Napoleonic army. The range of values is significant both in the number of armies and in the amount of losses.

Lecture on the losses of the Russian and Napoleonic armies, read in the church of St. mts. Tatians at Moscow State University

Archpriest Alexander Ilyashenko

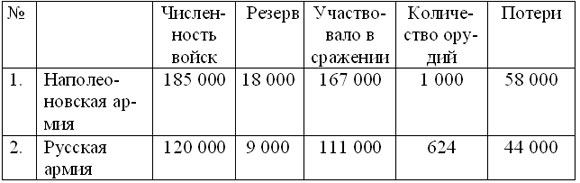

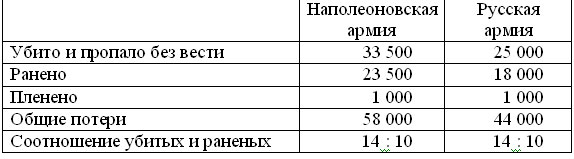

In the "Military Encyclopedic Lexicon" published in St. Petersburg in 1838 and in the inscription on the Main Monument installed on the Borodino field in 1838, it is recorded that under Borodino there were 185 thousand Napoleonic soldiers and officers against 120 thousand Russians. The monument also indicates that the losses of the Napoleonic army amounted to 60 thousand, the losses of the Russian - 45 thousand people (according to modern data, respectively - 58 and 44 thousand).

Along with these estimates, there are others that are radically different from them.

So, in the bulletin No. 18 of the "Great" army, issued immediately after the Battle of Borodino, the emperor of France defined the losses of the French as only 10 thousand soldiers and officers.

The spread of estimates is clearly demonstrated by the following data.

Table 1. Estimates of the opposing forces made at different times by various authors

Estimates of the sizes of opposing forces made at different times by different historians

A similar picture is observed for the losses of the Napoleonic army. In the table below, the losses of the Napoleonic army are presented in ascending order.

Table 2. Losses of the Napoleonic army, according to historians and participants in the battle

As we can see, indeed, the range of values is quite large and amounts to several tens of thousands of people. In table 1, the data of the authors, who considered the size of the Russian army to be superior to the number of Napoleonic ones, are highlighted in bold. It is interesting to note that Russian historians have joined this point of view only since 1988, i.e. since the beginning of perestroika.

The most widespread for the size of the Napoleonic army was 130,000, for the Russian - 120,000, for losses, respectively - 30,000 and 44,000.

As P.N. Grunberg, starting with the work of General MI Bogdanovich "History of the Patriotic War of 1812 according to reliable sources", is recognized for the reliable number of troops of the Great Army at Borodino, proposed back in the 1820s. J. de Chambray and J. Pele de Clozo. They were guided by the roll call data in Gzhatsk on September 2, 1812, but ignored the arrival of reserve units and artillery, which had replenished Napoleon's army before the battle.

Many modern historians reject the data indicated on the monument, and some researchers even cause irony. So, A. Vasiliev in his article “Losses of the French Army at Borodino” writes that “unfortunately, in our literature about the Patriotic War of 1812, the figure of 58,478 people is very often found. It was calculated by the Russian military historian V.A.Afanasyev based on data published in 1813 by order of Rostopchin. The calculations are based on the information of the Swiss adventurer Alexander Schmidt, who deserted to the Russians in October 1812 and passed himself off as a major who allegedly served in the personal office of Marshal Berthier. " One cannot agree with this opinion: "General Count Toll, based on official documents captured from the enemy during his flight from Russia, counts 185,000 people in the French army, and up to 1,000 pieces of artillery."

The command of the Russian army had the opportunity to rely not only on "official documents captured from the enemy during his flight from Russia", but also on the information of captured enemy generals and officers. For example, General Bonami was captured at the Battle of Borodino. British General Robert Wilson, who served with the Russian army, wrote on December 30, 1812: “There are at least fifty generals among our prisoners. Their names have been published and will undoubtedly appear in English newspapers. "

These generals, as well as the captured officers of the General Staff, had reliable information. It can be assumed that it was on the basis of numerous documents and testimonies of captured generals and officers in hot pursuit by domestic military historians that the true picture of events was restored.

Based on the facts available to us and their numerical analysis, we tried to estimate the number of troops that Napoleon brought to the Borodino field, and the loss of his army in the Battle of Borodino.

Table 3 shows the strength of both armies in the Battle of Borodino according to a widespread point of view. Modern Russian historians estimate the losses of the Russian army at 44,000 soldiers and officers.

Table 3. The number of troops in the Battle of Borodino

At the end of the battle, reserves remained in each army that did not take a direct part in it. The number of troops of both armies directly participating in the battle, equal to the difference in the total number of troops and the size of reserves, practically coincides, in terms of artillery, the Napoleonic army was inferior to the Russian one. The losses of the Russian army are one and a half times greater than the losses of the Napoleonic one.

If the proposed picture is true, then what is Borodin's day glorious for? Yes, of course, our soldiers fought bravely, but the enemy is braver, ours skillfully, and they are more skillful, our military leaders are experienced, and theirs is more experienced. So which army deserves more admiration? With this balance of power, the impartial answer is obvious. If we remain impartial, we will also have to admit that Napoleon won another victory.

True, there is some bewilderment. Of the 1,372 guns that were with the army that crossed the border, about a quarter were assigned to auxiliary sectors. Well, of the remaining more than 1,000 guns, only a little more than half was delivered to the Borodino field?

How could Napoleon, who deeply understood the importance of artillery from a young age, allow not all the guns, but only some of them to be put up for the decisive battle? It seems ridiculous to accuse Napoleon of his uncharacteristic carelessness or inability to ensure the transportation of weapons to the battlefield. The question is, does the proposed picture correspond to reality and is it possible to put up with such absurdities?

Such perplexed questions are dispelled by the data taken from the Monument installed on the Borodino field.

Table 4. The number of troops in the Battle of Borodino. Monument

With such a balance of forces, a completely different picture emerges. Despite the glory of a great commander, Napoleon, possessing one and a half superiority in forces, not only could not crush the Russian army, but his army suffered losses by 14,000 more than the Russian. The day on which the Russian army endured the onslaught of superior enemy forces and was able to inflict heavier losses on it than its own is undoubtedly the day of glory for the Russian army, a day of valor, honor, courage of its commanders, officers and soldiers.

In our opinion, the problem is of a fundamental nature. Or, to use Smerdyakov's phraseology, in the Battle of Borodino the “smart” nation defeated the “stupid” one, or the numerous forces of Europe united by Napoleon turned out to be powerless before the greatness of spirit, courage and martial art of the Russian Christian army.

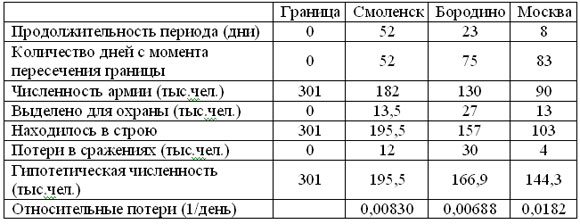

In order to better imagine the course of the war, we present data characterizing its end. The eminent German military theorist and historian Karl Clausewitz (1780-1831), an officer in the Prussian army who fought in the 1812 war with the Russian army, described these events in the 1812 Campaign to Russia, published in 1830 shortly before his death.

Drawing on Shaumbra, Clausewitz estimates the total number of Napoleonic forces that crossed the Russian border during the campaign at 610,000.

When the remnants of the French army gathered in January 1813 beyond the Vistula, “it turned out that they number 23,000 people. The Austrian and Prussian troops returning from the campaign numbered approximately 35,000 people, therefore, all together they amounted to 58,000 people. Meanwhile, the created army, including here and the troops that later approached, numbered in fact 610,000 people.

Thus, 552,000 people remained killed and captured in Russia. The army had 182,000 horses. Of these, counting the Prussian and Austrian troops and the troops of MacDonald and Rainier, 15,000 survived, therefore, 167,000 were lost. The army had 1,372 guns; the Austrians, Prussians, MacDonald and Rainier brought back with them up to 150 guns, therefore, over 1200 guns were lost. "

The data given by Clausewitz are summarized in a table.

Table 5. Total losses of the "Great" army in the war of 1812

Only 10% of the personnel and equipment of the army, which proudly called itself "Great", returned back. History does not know anything like that: an army more than twice superior to its enemy was utterly defeated by him and almost completely destroyed.

The emperor

Before proceeding directly to further research, let us touch on the personality of the Russian Emperor Alexander I, which has undergone a completely undeserved distortion.

The former French ambassador to Russia, Armand de Caulaincourt, a man close to Napoleon, who moved in the highest political spheres of the then Europe, recalls that on the eve of the war, in a conversation with him, the Austrian Emperor Franz said that Emperor Alexander

“They described him as an indecisive, suspicious and influenced sovereign; meanwhile, in matters that may entail such enormous consequences, one must rely only on oneself and, in particular, not go to war before all the means of preserving peace have been exhausted. "

That is, the Austrian emperor, who betrayed the alliance with Russia, considered the Russian emperor soft and dependent.

With school years many people remember the words:

The ruler is weak and crafty,

Bald dandy, enemy of labor

Then he reigned over us.

This false idea of Emperor Alexander, launched at one time by the political elite of Europe at that time, was uncritically perceived by liberal Russian historians, as well as the great Pushkin, and many of his contemporaries and descendants.

The same Caulaincourt preserved the story of de Narbonne, which characterizes the Emperor Alexander from a completely different perspective. De Narbonne was sent by Napoleon to Vilna, where the Emperor Alexander was.

“Emperor Alexander from the very beginning told him frankly:

- I will not draw my sword first. I do not want Europe to hold me responsible for the blood that will be shed in this war. I have been threatened for 18 months. French troops are on my borders, 300 leagues from their country. I am at my place for now. Fortifying and arming fortresses that almost touch my borders; send troops; incite the Poles. The emperor enriches his treasury and ruins individual unfortunate subjects. I stated that in principle I did not want to act in the same way. I don’t want to take money from the pockets of my subjects to put it in my own pocket.

300 thousand Frenchmen are preparing to cross my borders, and I still abide by the union and remain faithful to all the obligations I have assumed. When I change course, I will do it openly.

He (Napoleon - author) just called Austria, Prussia and all of Europe to arms against Russia, and I am still loyal to the union - to such an extent my reason refuses to believe that he wants to sacrifice real benefits to the chances of this war. I do not create illusions for myself. I value his military talents too highly to ignore all the risk to which the lot of war may expose us; but if I did my best to preserve the honorable peace and political system that can lead to universal peace, then I will not do anything incompatible with the honor of the nation I rule. The Russian people are not one of those who retreat in the face of danger.

If all the bayonets of Europe are gathered on my borders, they will not force me to speak in a different language. If I was patient and restrained, it was not because of weakness, but because it was the duty of the sovereign not to listen to the voices of discontent and to keep in mind only the calmness and interests of his people, when it comes about such big issues, and when he hopes to avoid a fight that could cost so many victims.

Emperor Alexander told de Narbonne that at the moment he had not yet assumed any obligation contrary to the alliance, that he was confident in his righteousness and in the justice of his cause and would defend himself if attacked. In conclusion, he opened before him a map of Russia and said, pointing to the distant outskirts:

- If the Emperor Napoleon decided to go to war and fate is not favorable to our just cause, then he will have to go to the very end in order to achieve peace.

Then he repeated once more that he would not be the first to draw his sword, but that he would be the last to put it in its sheath ”.

Thus, a few weeks before the outbreak of hostilities, Emperor Alexander knew that a war was being prepared, that the invasion army was already numbering 300,000 men, and he pursued a firm policy, guided by the honor of the nation he ruled, knowing that “the Russian people are not one of those who retreat in the face of danger. " In addition, we note that the war with Napoleon is not a war with France only, but with a united Europe, since Napoleon "called Austria, Prussia and all of Europe to arms against Russia."

There was no question of any "treachery" and surprise. The leadership of the Russian Empire and the command of the army had extensive information about the enemy. On the contrary, Caulaincourt stresses that

“Prince Ekmülsky, the General Staff and everyone else complained that they had not been able to obtain any information so far, and not a single intelligence officer had yet returned from that bank. There, on the other side, only a few Cossack patrols were visible. The emperor inspected the troops in the afternoon and once again took up reconnaissance of the surroundings. The corps on our right flank knew no more of the enemy's movements than we did. There was no information about the position of the Russians. Everyone complained that not one of the spies was returning, which greatly annoyed the emperor. "

The situation did not change even with the outbreak of hostilities.

“The king of Naples, who commanded the vanguard, often made day trips of 10 and 12 leagues. People did not leave the saddle from three in the morning until 10 in the evening. The sun, almost never descending from the sky, made the emperor forget that a day has only 24 hours. The vanguard was reinforced by carabinieri and cuirassiers; horses, like people, were exhausted; we lost a lot of horses; the roads were covered with horse corpses, but the emperor every day, every moment cherished the dream of overtaking the enemy. At any cost he wanted to get the prisoners; this was the only way to get any information about the Russian army, since it could not be obtained through spies, who immediately ceased to bring us any benefit as soon as we found ourselves in Russia. The prospect of the whip and Siberia froze the ardor of the most skillful and most fearless of them; to this was added the real difficulty of penetrating the country, and especially into the army. Information was received only through Vilno. Nothing came directly. Our marches were too long and too fast, and our too exhausted cavalry could not send out reconnaissance detachments or even flank patrols. Thus, the emperor most often did not know what was happening two leagues from him. But no matter what price was attached to the capture of prisoners, it was not possible to capture them. The Cossacks had a better guard than ours; their horses used the best care than ours, they turned out to be more resilient in the attack, the Cossacks attacked only when the opportunity arises and never got involved in battle.